Honorary Curator Elizabeth Searle Lamb

Elizabeth Searle Lamb

Honorary Curator, 1996–1998

Biography

by Miriam Sagan

Elizabeth Searle Lamb was a major voice in the world of English-language haiku. She won more than 150 awards in the haiku field and her work was translated into Japanese, Chinese, Polish, French, and Spanish, among other languages. As a haiku poet, her work is more firmly influenced by place than by any other source of inspiration, although art, music, nature, and the passing scene of human life are also crucial. Her travels around the world, particularly the years spent in Latin America and New York City, were a central source for her haiku. And so was the opposite experience of living for thirty years in one quiet place on Santa Fe’s Acequia Madre, or Mother Ditch.

She was born Elizabeth Louise Searle on January 22, 1917, in the American heartland of Topeka, Kansas. One of her first memories was about the power of words. As a pre-kindergartner she lay on the floor picking out words she could recognize from the newspaper and circling them in an attempt to learn to read. Music was also an early influence. As a sixth grader she heard a solo harpist play and was smitten with the instrument. Her grandmother bought her a harp, and Lamb went on to study music at the University of Kansas.

It was there that she met her future husband. Bruce was a flutist, and the two were soon playing together. Upon graduation, he joined the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and was shipped off to Trinidad, B.W.I. After Elizabeth agreed to marry Bruce, she took a train, a freighter, and a small airplane to arrive on the island of Trinidad four days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. They were married, spent two years on the island, and then as Elizabeth said: “the harp went back to Kansas and we went to Brazil and up the Amazon.”

This exotic voyage proved to be Elizabeth Lamb’s genesis as a writer. As she described it, “while Bruce explored and developed sources for the wild rubber necessary for the war effort, I lived in a very primitive small town, Santarem, often the only person there who spoke English. Bruce was back up the Tapajos River three weeks out of four.” Elizabeth had a small manual typewriter and began to write and publish travel, music, and inspirational articles.

Her daughter Carolyn was born in 1944, and the family lived in Guatemala, Costa Rica, Honduras, Puerto Rico, Panama, and Columbia.

Elizabeth Searle Lamb's passport photo from the early 1950s.

In 1961 they moved to Greenwich Village in Manhattan, where Elizabeth became acquainted with the group that would become the Haiku Society of America, under the early leadership of Professor Harold G. Henderson. She was a charter member of this organization when it was founded on October 23, 1968.

Elizabeth began publishing her haiku regularly in American Haiku (founded 1963), Haiku West (1967), and Modern Haiku (1969). She was an early president of the Haiku Society and went on to edit the society’s magazine Frogpond for almost eight years. In 1975, Bruce took early retirement and they returned to Elizabeth’s Kansas home for two years. After settling her family’s affairs, they moved to an old adobe house that Elizabeth always described as “funky” beside the acequia in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Bruce wrote his best known book, a classic of ethnobotany, Amazon adventure, psychedelic drugs, and shamanism: The Wizard of the Upper Amazon. The fame of this book brought an interesting stream of visitors from hippies to professors.

Starting in 1975, Elizabeth began publishing small chapbooks that were eventually collected in Across the Windharp (La Alameda Press, 1999). In his preface to the book, William J. Higginson writes that, “beyond craft, beyond exotic scenery and subjects, a central peace—a deep resonance with life as it simply is—permeates this work.”

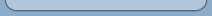

Elizabeth Searle Lamb at her writing desk, around 1976, in Topeka, Kansas. The typewriter was a Smith Corona manual that she held onto as long as she could keep it going. After moving to Santa Fe she found a repair place that could repair it for her, but eventually they went out of business.

In 1992, when Bruce Lamb died, Elizabeth moved across her own driveway to another charming small house while her daughter Carolyn moved into the original house along with her husband.

In 1996, when the California State Library opened its American Haiku Archives, Elizabeth Searle Lamb was named the first honorary curator. Her work is archived in the collection, and she was the primary original donor of material for the collection.

Elizabeth Searle Lamb at the door to her home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, taken in December of 1998.

When she was in her late eighties I asked her for some guidance on a class I was teaching on haiku. What advice should I give the students, I wanted to know. “I do what I like,” Elizabeth said, a somewhat surprising answer. However, Higginson characterizes her work as “a tighter, snappier kind of haiku” that included willingness to experiment and “an approach based on organic form.” In this, as in the earlier free verse she wrote before she discovered haiku, she was a true modernist. She was also a friend in haiku and informal mentor to many other writers.

Lamb’s creative process included keeping a yearly journal that was part diary, part writer’s notebook, and also contained postcards and other ephemera pasted in for inspiration. She kept folders of ideas of everything from Christmas cards to newspaper articles. As an octogenarian she would often wake in the middle of the night and scribble down a haiku straight out of a dream. On her death, she left haiku written on index cards, on a night table stack, and scribbled on bits of paper around the house—evidence of a rich ongoing writing process.

Elizabeth died on February 16, 2005. One of the ways she worked with haiku was to write variants, not drafts exactly but rather more than one way of looking at a subject. Among her papers were the following:

will I be able,

when that time comes,

to write my own death haiku

and

when that day comes

will there be one moment

for my own death haiku?

In her long practice of writing haiku, senryu, tanka, haibun, and renku, she remained focused on capturing the moment, on the interplay between inner and outer worlds.

Photographs courtesy of Carolyn Lamb.

Books by Elizabeth Searle Lamb

In this Blaze of Sun. Patterson, New Jersey: From Here Press, 1975.

Picasso’s Bust of Sylvette. Topeka, Kansas: Garlinghouse Printers, 1977.

39 Blossoms, Battle Ground, Indiana: High/Coo Press, 1982.

Casting into a Cloud: Southwest Haiku. Fanwood, New Jersey: From Here Press, 1985.

Lines for My Mother, Dying. Glen Burnie, Maryland: Wind Chimes, 1988.

Ripples Spreading Out: Poems for Bruce and Others. Enfield, Connecticut: Tiny Poems Press, 1997.

Across the Windharp: Collected and New Haiku. Albuquerque, New Mexico: La Alameda Press, 1999.

See the American Haiku Archives records of Elizabeth Searle Lamb publications available in the American Haiku Archives: AHA-Holdings-ElizabethSearleLamb.pdf.

Selected Haiku by Elizabeth Searle Lamb

the year turns—

on the harp’s gold leaf

summer’s dust

New Year’s Day

a tiny glass angel

catches a sunbeam

deep in this world

of Monet water lilies . . .

no sound

a year older now,

Picasso’s “Bust of Sylvette”

in the square

in the winter moonlight

an owl in the old pine

echoes flute notes

Christmas morning

last night’s farolitos

sag on the wall

a plastic rose

rides the old car’s antenna—

spring morning

leaving the cabin

I put the old calendar

into my backpack

so quiet

after the tea ceremony

hazy moon

I cross the courtyard—

shadow of ravens, flying

beneath my feet

the apricot

in full bloom—O’Keeffe’s

black sculpture

whispers

of ancient water-song

the Red Planet

The first ten haiku are from Across the Windharp: Collected and New Haiku (Albuquerque, New Mexico: La Alameda Press, 1999). The last two poems are uncollected, courtesy of the estate of Elizabeth Searle Lamb.

Web Links

Millikin University Haiku Writer Profile, Elizabeth Searle Lamb

http://www.brooksbookshaiku.com/MillikinHaiku/writerprofiles/lamb.html

Dreamcatcher of Light (Santa Fe Poetry Broadside, 2002)

http://www.sfpoetry.org/june2002.html

The Time Flows Poems (Santa Fe Poetry Broadside, 2005, In Memoriam)

http://www.sfpoetry.org/september2005.html

Natalie Kussart essay on Elizabeth Searle Lamb